I

If India is to once again take her place as a great nation inspiring others with her values and way of life, she has to place the artistic culture1 and its education at the heart of her developmental policies. This can only be made possible if the intelligentsia and creative community builds the infrascape (ie: the artistic environment and its underlying material infrastructure) on their own terms, while placing the values of artistic creativity and its integrity at the heart of this process. The nature and scale of the change required is radical, yet now increasingly inevitable.

The change demands that various individuals re-institutionalize a vast integrated intellectual framework which builds the platforms upon which the intelligentsia can cohesively come together, nurturing each others efforts while generating and redistributing significant amounts of economic wealth, to forward this exercise of directly transforming creative idealism into its material formats.

This additional responsibility of generating wealth and its simultaneous redistribution is pivotal, demanding a new understanding and approach. It is time to wean away the creative community from all the traditional modes of patronage: government support, corporate sponsorship and private donations, towards a new alternative system of far greater financial independence. This implies restructuring the basis by which artistic culture and its educational institutions are built, which in turn demands a critical reconsideration of the role the artist-scholar-activist is to play in this process.

In the past the duty of generating economic wealth so as to help bring to public awareness their own creativity, let alone any wider display, was always abdicated by the artist. Yet they eagerly sought participation in the process of wealth redistribution. The government has been brought to its financial knees in the area of cultural and educational expenses because of this dependency of the intelligentsia & creative community. In recent years the more savvy artists, seeking middle-players, have run to the corporate houses for patronage, calling it sponsorship and in the process selling their creative wines, barely re-labeling the bottles. Those galleries or genuine patrons who tried to disseminate creative ideals to the public were far and few between, leaving huge lacunae for the more mercurial wheeler-dealer agent system to slowly infiltrate the mindset. To some extent this has natural benefits, but on its own the present system is totally incapable of tackling any wider vision concerning the role of the arts in the developmental policies of India.

II

At the heart of all institution-building efforts is the art of materially transforming individual brilliance and inspiration into a system, for others to specialize, deepen and widen, and there-after delegate and integrate a whole stream of activities, which hopefully move in harmony with the original vision and its inbuilt evolution. However, the process of delegation and dissemination is deeply flawed and inadequate, especially for the arts, and more so for India, given the superficial relationship that exists between the artist-scholar-activist and their responsibilities towards wealth generation and its implied redistribution. Also, numerous contradictory hidden agendas are built into the process of nurturing artistic creativity and of building art institutions. These range from the nature and role of patronage to the limited practical grasp given to integrating cultural disciplines in the holistic manner by which they exist within creativity, to the direct responsibility upon the artist-scholar-activist in building and sustaining the institutions, and then letting go and pasing on responsibility.

Further, it is totally inadequate to only have specialized personnel for the management of artistic culture, especially if they are not first and foremost artistic and creative minds. It is also not enough to have artists who are in their last phase of creative life, and are part of various advisory committees and boards, involved with cultural institution building. Hence, it is paramount that the young and energetic artistic minds who can create the finest works of art, literature, cinema, theatre, philosophy, music and the like, dedicate a part of their day and life to building the material infrastructure which nurtures the creativity of all. Without this input, that overwhelming creative idealism, as a collective force, will not inculcate itself into the system with the new creative attitude so essential to re-mould the priorities and mindsets with which we structure society and allocate scarce resources.

This is not the place to detail the nature of this creative attitude. However, the main human characteristic which sustaining one’s creative urge reveals is the ability to play with uncertainty, to give freedom to uncertainty. All individuals on a daily basis interact with the uncertain, the art is to allow uncertainty to reveal herself. The creative individual learns how to hold back and discipline one’s preconceptions long enough for the tussle between answer and question to open out another unseen perspective. It is always this additional perspective, rooted in a surprise, which takes one closer to a truth, or more importantly, allows one to sustain the search for a truth. It is this exploratory open-mindedness, this confidence and inner security to test the unknown against one’s convictions with a humble wisdom, which is at the heart of the genuine creative impulse. From this play with uncertainty comes the respect for experiment, nurtured by the constant inner dialogue, leading to the joyous giving of freedom to others, which in turn cannot help but make compassion the underlying emotion of all communication. From herein emanates the roots of a possible ethical framework.

It will be from implicitly nurturing the ethical implications of this joyous self-critical attitude, that slowly over time, the process of allocating scarce resources will subtly change, weaning itself away from the overriding economic & its related power compulsions which today dictate the growth of society and its structures. However, the socio-political implications of allowing the above changes will be discussed at a later date.

III

Ironically, despite the deeper respect for financial value, the chances of a counter discipline (to the economic value system) emanating from the values inherent in the artistic creative process seems more likely to occur in Europe than a country such as India. At the same time, given India has not gone through a significant phase of material wealth accumulation, she still possesses a relatively blank set of preconceptions and minimal intruding baggage, on one level.

Thus, with relatively little experience in the pursuit of transforming idealism into material formats, especially within the arts, she has the advantage of being an outsider to the process, so capable of seeing the whole vision, more objectively, hence capable of acting faster and with greater clarity. This potentially allows her greater innovation and experimentation in institution-building, if only the atmosphere nurtures such risk-taking. Yet given mainstream religious motivation has been the most successful examples of institution-building in India, the chances of sustaining a radically different infrascape developmental process will not be easy.

Building a credible infrascape firstly demands forcing and cajoling the economic system into placing the arts and artistic culture at the heart of socio-political developmental policies. For this to be, the artistic community and intelligentsia will have to show the rest of the nation that they are indeed capable of building the basic level infrastructure for the arts, on their own terms. Further, that these terms respect and privilege the artistic creative process and its integrity beyond all else, and that while maintaining this integrity one is capable of generating and simultaneously redistributing vast wealth, better than competing alternatives.

This implies creating new paths away from, yet linked to, the traditional modes of patronage adopted across the world: government support, corporate sponsorship and private philanthropy. It is thus imperative that the creative community, not only generates wealth, but more importantly redistributes this wealth more effectively, than any other mode. In fact one cannot divorce both aspects. From the starting point of earning wealth a significant proportion must be ploughed back into the wider infrastructure-building task. This is the duty of each individual. To pay taxes is just one part of that duty; each individual must get into the habit of taxing themselves, through their own inner discipline, recognising the state of the country, its wider problems, and one’s creative and moral obligation.

It is a desperate need of the times; no more is infrastructure-building the duty of the other, or some paternal state. Each individual must recognize that irrespective of circumstances and position, each has the power to bring about change, not just indirectly by doing one’s work, but more directly by absorbing a wider vision required for infrastructure-building and trying to be true to fulfilling one’s role within that scheme. In this restructuring of duties, where the artistic and clerical overlap, the profound and mundane embrace, we begin to open new dimensions for redefining the role of the intelligentsia, at every level.

For example, by the act of meaningfully positioning (amid a curatorial exhibition space or within the structure of a publication or some virtual reality option) a Deewaar poster, with all its loud colours, seething energy and emotional links, ‘besides’ the tranquil contemplation of a Gaitonde watercolour, many new and unseen inter-relationships will open up, naturally changing the perception of each in the process. Further, the act will cut through various preconceptions if the juxtapositioning reveals a unity which existed, but was denied or suppressed, yet now seems obvious and necessary to explore further. Similarly, the duties before the artist-scholar in the field of putting together the material platforms upon which debate and dialogue, learning and rediscovery, sale and purchase, appreciation and criticism, are nurtured, require a new juxtapositioning and reprioritising.

On another level, many new options of funding cultural projects can arise if the complex nature of intellectual and financial cross-subsidization can be viewed afresh.The nature of this cross-subsidization will in turn depend upon the ability of scholarship to reinterpret and re-express knowledge and the various inter-linkages between all the cultural disciplines, into an effective communicative instrument whereby the links between what has been traditionally associated with the inner & introspective and pure (untainted by outer material obligations) aspects of the creative process and the outer more compromised aspects of the material environment and influences are re-established. For example, who could have imagined that from a handful of curated auctions of modern Indian art one individual would have been able to institutionalize the world’s largest photographic and textual archive on Indian Modern & Contemporary Fine Arts and Cinema, within the span of a few years, without resorting to government support, corporate sponsorship or donations, and at the same time without significantly involving the academic establishment and bureaucracy, while simultaneously evolving the seeds of a new platform which could potentially tackle the corrupt practices which have led to the suppression of one of the world’s greatest cultural heritage’s.

I use this example, not to praise, but just to indicate, that despite the most stubborn of preconceptions on my part, which firmly believed, until the age of thirty-five, that wealth was not an important ingredient in building great educational institutions, and that vision, hard work and the ability to inspire others was enough, India has allowed one to move forward with relative swiftness. This freedom, rarely recognised or given appreciation, especially when compared to western standards, is nonetheless available in few other countries, with the emotional intensity and warmth as in India. This alone is capable of institutionalising love and its family of values into the framework for nurturing the infrastructure for the Indian arts and culture.

Building the Infrascape

October 2001

The task before the intelligentsia and creative community is to build an environment in which the ideal material system can hope to flourish. For this environment to be sustainable and desired by our people, the creative community must have a significant material stake in the system, i.e. in the infrastructure and institutions, which nurtures the environment on a daily basis. This stake in the infrastructure-building process simultaneously demands creative inputs at both the levels of maintaining the integrity of the idealistic vision and taking on the responsibility for the financial self-sufficiency of the process.

Thus creating this infrascape2 is no longer about a division of activity where idealism is the duty of one set of creative minds and the wealth generating and redistributing obligations burdened upon another set of implementing organizations. A fundamental redefinition of the Arts & Cultural Institution is now inevitable, as is the duty demanded from an artistic creative individual and the intelligentsia as a collective force.

One requirement of this new duty is the need to recreate or re-mould the mechanisms and terms by which economic wealth is to be generated and simultaneously redistributed in a more effective manner. This in turn demands a reassessment of all forms of patronage - governmental, corporate and philanthropic, and the possibility of the arts generating wealth for their own infrastructure-building efforts. It also demands a deeper debate, asking: can the creative integrity maintain its obsessive focus, its inspirational force to a wider humanity, when it suddenly places itself amid material obligations and all the distractions of administration and the pursuit of material power?

Another implied responsibility of building the infrascape becomes the task of documenting, preserving and restoring to daily life our artistic and cultural heritage. This in turn opens out a vast educational responsibility. Also, from nurturing and harnessing this heritage and knowledge base emerges the possibility, if undertaken with the integrity of an infrastructure-builder, the possibility of generating and redistributing significant amounts of wealth – aesthetic and economic, and thereby tackling one of the fundamental dilemmas facing the whole task.

This task, ideally to be fulfilled in partnership with government, requires a holistic vision which was once the privilege of government, but now must become the responsibility of the private sector. Recent introspection regarding its role in the cultural arena and a greater recognition of its fiscal imperatives is placing the government in a growingly difficult position. On one level it seeks greater influence in the infrascape, on another all major archives, heritage properties and educational facilities are facing a significant loss of motivation, confidence and resources. In the process the respect for merit and a belief in intellectual integrity and freedom is suffering. Corporate sponsorship will brand the heritage belonging to the public, and in the process persuade that all creative, aesthetic, intellectual and historical efforts are now but another commodity to be purchased. This in turn will negate the potential impact of increasing respect for creativity and its family of values, which in turn lessens the chances of providing the economic value system with a counter-discipline.

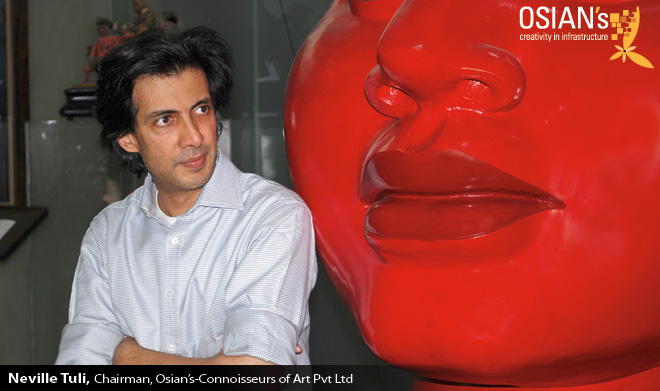

Criticising this whole scenario is now easy and pointless, unless a viable alternative is possible and offered. Obviously, the chances of a sustainable alternative exist. On an individual level, one has sowed the seeds of an institutionalizing process which may be able to implement an alternative infrascape-building process, away from the dependence on the usual forms of patronage and their conditions. Of course, the process is still in its infancy, and failure is as likely as success. Osian’s will fulfil its duty. Others will follow and deepen the process. Momentum and progress are inevitable.

1 The arts, artist, artistic, or any similar form is used with the broadest sense of the meaning for the arts, ranging to include the Fine Arts to Cinema, from Philosophy to Music.

2 Infrascape seems an apt word to describe both the environment and its underlying infrastructure for the arts and culture.

Monday, March 30, 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment